Syll has a really great Keynes quote (28 June), on the "belief that there is some law of nature which prevents men from being employed". Unreferenced, so I looked it up. Ended up at Wikipedia's Full employment page. They attribute the quote to "J.M. Keynes in a pamphlet to support Lloyd George in the 1929 election." With that out of the way now ...

The wiki page opens with these words:

Full employment, in macroeconomics, is the level of employment rates where there is no cyclical or deficient-demand unemployment. It is defined by the majority of mainstream economists as being an acceptable level of unemployment somewhere above 0%. The discrepancy from 0% arises due to non-cyclical types of unemployment ...

And then comes the part where bells go off in my head:

Unemployment above 0% is seen as necessary to control inflation in capitalist economies, to keep inflation from accelerating, i.e., from rising from year to year. This view is based on a theory centering on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) ...

This is why the bells were ringing: When I got my three credits in macro, back in the late 1970s, I was taught that one of the goals of economic policy was price stability. But since I've been internetting, the universally accepted current version of that goal seems to be inflation stability. As opposed to price stability.

The reason for this change became suddenly obvious to me as I read the wiki words: "This view is based on a theory centering on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) ..."

The NAIRU got somehow turned around and used as the basis for saying that inflation is okay, even though accelerating inflation is not. There is no logical argument for that conclusion, that I can see. But the NAIRU is the only explanation I have found for the change from "price stability" to "inflation stability".

So if you are in favor of a little inflation or maybe a little more inflation as economic policy, let me just point out that the full force and power of the NAIRU stands behind your thinking.

That should make you think again.

My view? The goal remains price stability. I recognize that inflation can "erode" debt, in a manner of speaking. I recognize that inflation can have "beneficial" effects for the economy. But I do not and cannot accept the notion that we can or should or might use inflation as a policy tool. The ends do not justify the means.

In all my internet years, the only person I've seen say anything comparable to the view I express is John Cochrane:

The Fed currently interprets "price stability" to mean 2% inflation forever. A CPI standard could enforce 2% inflation. But why not establish a price-level target instead? The CPI could be the same 30 years from now as it is today, and long-term contracts could carry no inflation risk.

I don't know how good his math is. If a CPI standard could enforce 2% inflation, then it could enforce 0% inflation. And that would give you price stability without specifically establishing a "price-level target". I don't know: Maybe he just phrased it that way for emphasis. If I can do the math in my head, I'm sure he can.

Maybe this one is better:

The euro is the unit of value, as the hour is the unit of time and the meter is the unit of value. You could engineer a one-time boost by fiddling with the hour, the meter, the kilo and the euro. Until people catch on ...

Anyone for a drink?

Yeah, me.

Farther from topic: John Cochrane asks why we don't go with zero inflation, rather than two percent. The answer, John, is that we would have to replace inflation with some other policy that helps keep private debt down and provides some of the other good effects as well.

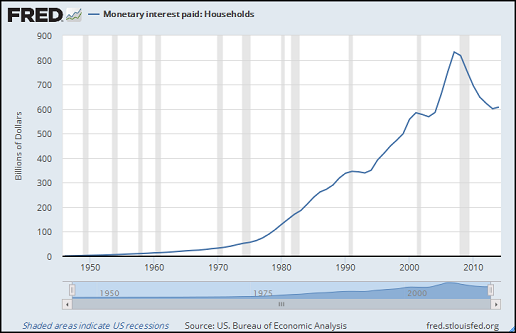

Nobody seems to know what that policy might be. So I'll say it again: We have to start eliminating the policies that encourage credit use and debt accumulation. We have to start creating policies that encourage credit use and the repayment of debt. It's not a big change. It wouldn't be difficult to do. The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds.